- The Dominant Player: Sedimentary Rocks

- Understanding Why Sedimentary Layers Form

- Metamorphic Rocks: Layers Under Pressure

- Exploring Why Metamorphism Creates Layered Textures

- Igneous Rocks: Less Common, Still Possible

- What the Layers Tell Us: A Window into Earth's Past

- Why Geologists Study Rock Layers

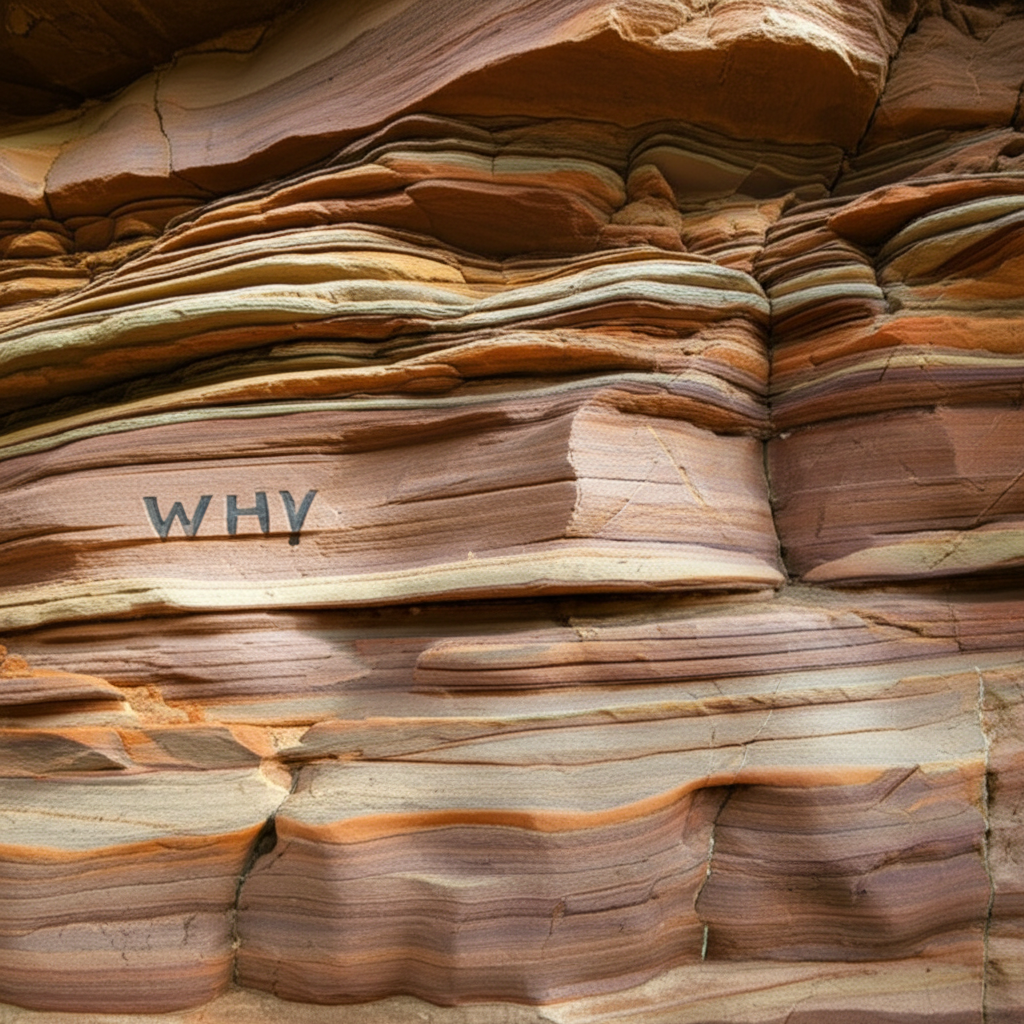

Why do rocks have layers? This seemingly simple question unlocks a profound understanding of Earth’s dynamic history, revealing countless tales etched in stone over millions, even billions, of years. From grand canyon walls to humble riverside outcrops, the distinct stratifications in rocks are not just beautiful patterns; they are geological narratives, a fundamental record of our planet’s ever-changing surface and interior processes. Understanding the mechanisms behind these layers provides stunning and clear answers, illustrating the Earth as a living, breathing system of creation and transformation.

The vast majority of layered rocks we observe are sedimentary rocks. These are formed from the accumulation and compaction of sediments – fragments of other rocks, minerals, or organic matter – that have been weathered, eroded, transported, and finally deposited. The process is a continuous cycle, shaped by forces like wind, water, ice, and gravity.

The Dominant Player: Sedimentary Rocks

Imagine a river carrying a mix of sand, silt, and clay. As the river flows, it sorts these particles based on their size and density. When the river slows down, perhaps entering a lake or the ocean, the heavier, larger particles (like sand) settle out first, followed by lighter, finer particles (like silt and clay), and eventually microscopic organic matter. This differential settling is the primary reason why sedimentary rocks form distinct layers.

Over time, countless layers of these sediments accumulate, one on top of the other. Each layer, or “stratum,” represents a specific period of deposition, under particular environmental conditions. A change in these conditions – perhaps a flood introducing coarser sand, a period of drought leading to finer clay, or an influx of marine organisms building up shell fragments – creates a new, distinct layer.

Understanding Why Sedimentary Layers Form

The formation of layers in sedimentary rocks is a fascinating display of Earth’s surface processes.

1. Weathering and Erosion: Existing rocks are broken down by physical (e.g., freeze-thaw cycles) and chemical (e.g., acid rain) weathering. These fragments are then eroded and transported by agents like rivers, glaciers, wind, and ocean currents.

2. Deposition: As the transporting agent loses energy, the sediments are deposited. Heavier sediments settle first, followed by lighter ones. This often results in a graded bedding, where coarse grains are at the bottom of a layer and finer grains at the top. Different types of sediment (e.g., sand, mud, shells, volcanic ash) will form distinct layers due to changes in source material or environmental conditions.

3. Compaction and Cementation (Lithification): As more layers accumulate, the weight of the overlying sediments compresses the lower layers, squeezing out water. Chemical precipitation of minerals like calcite, silica, or iron oxides then acts as a natural glue, cementing the individual grains together, transforming loose sediment into solid rock. Each “event”—a flood, a drought, a shift in sea level—leaves its mark as a new layer.

Think of shale, composed of compacted mud, or sandstone, formed from cemented sand grains. The alternating light and dark bands, or changes in grain size and composition, perfectly illustrate the varying depositional environments experienced over geological time. A sudden surge in river flow might deposit a thick layer of coarse sand, while a subsequent calm period might see fine silt gradually settling, creating a clear demarcation between the two strata.

Metamorphic Rocks: Layers Under Pressure

While sedimentary rocks are the poster children for layering, metamorphic rocks also exhibit a form of layering known as foliation. Metamorphic rocks are formed when existing rocks (igneous, sedimentary, or other metamorphic rocks) are subjected to intense heat and pressure, causing their mineral composition and texture to change without completely melting.

Exploring Why Metamorphism Creates Layered Textures

Foliation occurs when immense pressure, often directed from specific sides, causes the platy or elongated mineral grains within a rock to reorient themselves perpendicular to the direction of the stress. Imagine squashing a ball of clay containing tiny flakes; the flakes will flatten and align themselves in planes parallel to the applied force.

This reorientation creates a distinct, parallel arrangement of mineral grains or textural features, giving the rock a layered or banded appearance. Examples include:

Slate: Formed from shale, its fine grains are aligned to create excellent cleavage, allowing it to split into thin, flat sheets.

Schist: With coarser grains than slate, its parallel alignment of mica minerals gives it a sparkling, scaly appearance.

Gneiss: Formed under even higher temperatures and pressures, gneiss displays distinct light and dark bands of minerals (e.g., quartz and feldspar alternating with amphibole and mica), known as gneissic banding. These layers are often contorted and folded, reflecting the incredible forces they endured.

Igneous Rocks: Less Common, Still Possible

Igneous rocks, formed from the cooling and solidification of molten rock (magma or lava), typically do not exhibit layers in the same way as sedimentary or metamorphic rocks. However, there are exceptions:

Layered Intrusions: In very large magma chambers, different minerals may crystallize and settle at different rates as the magma cools slowly over millennia. This process, called fractional crystallization, can lead to distinct layers of different minerals accumulating on the floor of the chamber, forming spectacular layered igneous intrusions like the Bushveld Complex in South Africa.

Flow Banding: In some lava flows, especially viscous ones, the differential movement of the molten rock can create parallel bands or swirls, giving the rock a layered appearance.

Volcanic Ash Deposits (Tuff): When volcanoes erupt explosively, they can deposit layers of ash and fragments (tephra) that settle out of the air or flow across the landscape in a manner similar to sediment, leading to stratified volcanic rocks.

What the Layers Tell Us: A Window into Earth’s Past

Beyond their formation, rock layers are invaluable archives of Earth’s history. They act as a geological timeline, with the oldest layers generally found at the bottom and the youngest at the top (a principle known as superposition, assuming no tectonic disturbance).

Why Geologists Study Rock Layers

Geologists meticulously study rock layers for a multitude of reasons:

Past Environments: The type of sediment in a layer reveals the ancient environment. Sandstone might indicate an ancient desert or beach, while shale suggests a calm lake or deep ocean. Limestone points to a marine environment rich in shell-forming organisms.

Climate Change: Alternating layers of different types can signal shifts in past climates, from glacial periods to warmer, wetter conditions, or even major droughts.

Catastrophic Events: Layers can preserve evidence of major events like volcanic eruptions (ash layers), meteor impacts (iridium-rich layers), or massive floods.

Fossils: Fossils found within sedimentary layers provide direct evidence of ancient life, allowing scientists to piece together the history of evolution and the biodiversity of past ecosystems.

* Resource Exploration: Understanding the sequence and characteristics of rock layers is crucial for locating valuable resources such as oil, natural gas, coal, and groundwater.

Each layer holds clues about the conditions on Earth at the time it was formed—the strength of the currents, the type of life present, the climate, and even the chemical composition of the atmosphere or oceans. They paint a vivid picture of a planet that never stops changing, constantly rebuilding itself layer by layer.

In conclusion, the enchanting layers found in rocks are not mere curiosities but profound expressions of geological processes. Whether it’s the slow, steady deposition of sediments, the intense pressure and heat of metamorphism, or the rare but striking stratification within igneous bodies, each layer serves as a testament to the Earth’s enduring dynamism. These stunning markings are clear answers to why our planet is perpetually recording its saga, one stratum at a time.

0 Comments