- What Exactly Are Tectonic Plates?

- The Driving Force: Why Do Tectonic Plates Move?

- Where Tectonic Plates Meet: Plate Boundaries

- The Profound Impact of Tectonic Plates on Earth's Surface

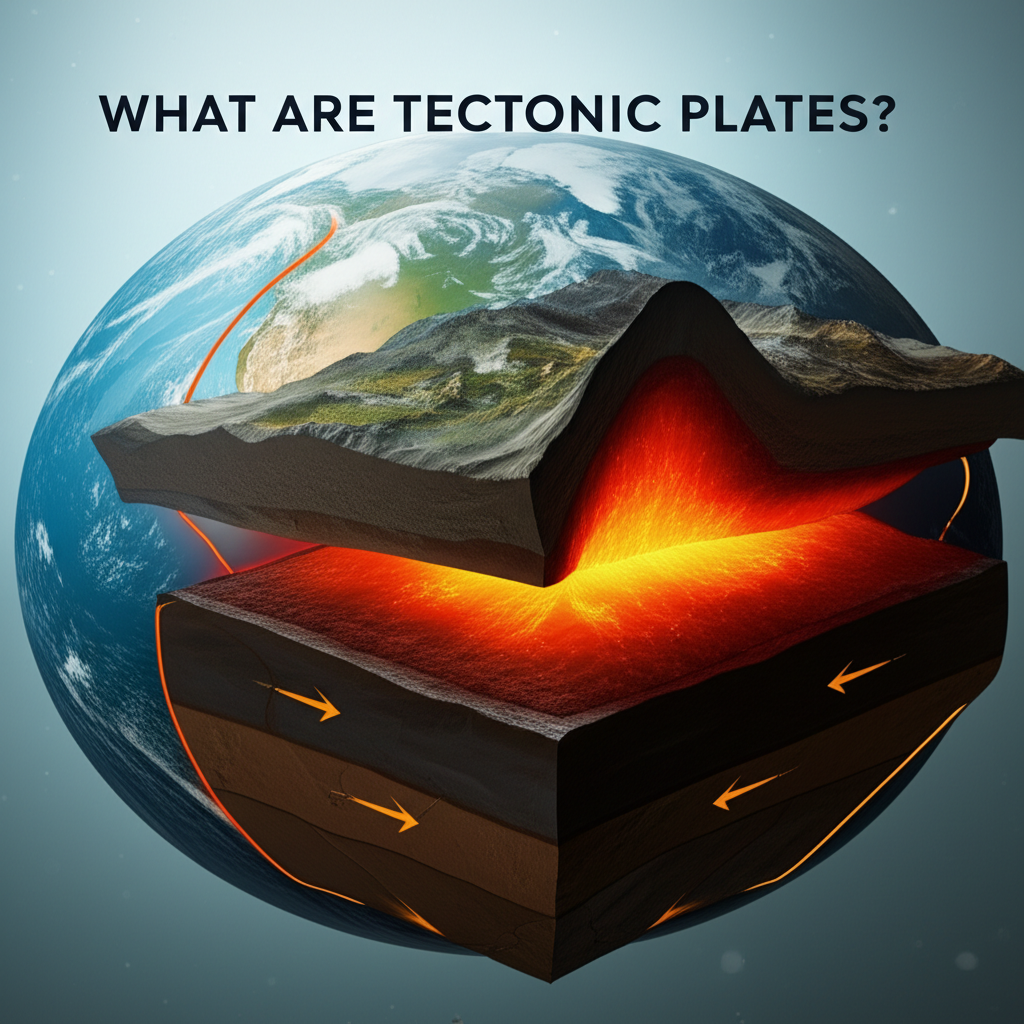

What lies beneath our feet, constantly shifting and shaping the world as we know it? The answer is tectonic plates. These colossal, interlocking pieces of the Earth’s outer shell are the silent architects of our planet’s most dramatic features, from towering mountain ranges to deep ocean trenches, and the restless instigators of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Understanding tectonic plates is fundamental to grasping the dynamic nature of Earth and the powerful forces that continually reshape its surface.

What Exactly Are Tectonic Plates?

At its core, Earth is a layered planet, much like an onion. The outermost layer is the lithosphere, a rigid shell that includes the Earth’s crust and the uppermost part of the mantle. It’s this lithosphere that is broken into several large and numerous smaller pieces – these are the tectonic plates. These plates aren’t merely fragments of the surface; they extend deep into the Earth, floating on a hotter, denser, and more viscous layer of the mantle called the asthenosphere. Think of them as giant rafts of rock, slowly navigating a super-thick, semi-molten sea.

There are approximately 7-8 major tectonic plates (like the Pacific Plate, African Plate, Eurasian Plate, etc.) and many more minor ones. These plates are not uniformly thick. They consist of two primary types of crust:

Oceanic crust: Thinner (5-10 km), denser, and primarily composed of basalt. It underlies the world’s oceans.

Continental crust: Thicker (up to 70 km), less dense, and predominantly made of granite. It forms the continents and continental shelves.

The interaction and movement of these diverse sections are what drive much of Earth’s geological activity.

The Driving Force: Why Do Tectonic Plates Move?

The seemingly slow, majestic movement of tectonic plates is powered by immense forces originating deep within the Earth. The primary engine behind this planetary ballet is mantle convection. Imagine a pot of boiling water: as water heats up at the bottom, it becomes less dense and rises, cools at the surface, becomes denser, and sinks, creating a continuous circulatory pattern. The Earth’s mantle, though far more viscous than water, behaves similarly over geological timescales. Heat from the Earth’s core causes molten rock (magma) in the lower mantle to become less dense and slowly rise. As it approaches the lithosphere, it cools and spreads laterally, dragging the overlying tectonic plates with it, before eventually sinking back down.

Adding to this convection are two other significant forces:

Ridge Push: At mid-ocean ridges (divergent boundaries where new crust is formed), the lithosphere is elevated and hotter, causing it to effectively “slide” downhill away from the ridge under the force of gravity, pushing the plate ahead of it.

Slab Pull: This is considered the strongest driving force. When oceanic plates collide with other plates and sink into the mantle at subduction zones (convergent boundaries), the dense, cold slab of rock effectively “pulls” the rest of the plate along behind it, much like a heavy anchor descending into water.

These forces combine to move plates at speeds ranging from a mere 1-2 centimeters per year (about the rate your fingernails grow) to around 10-15 centimeters per year. While slow, these movements accumulate over millions of years to dramatically alter the face of our planet.

Where Tectonic Plates Meet: Plate Boundaries

The most intense geological activity occurs at the boundaries where tectonic plates interact. There are three main types of plate boundaries, each associated with distinct geological phenomena:

1. Divergent Boundaries:

Here, plates are pulling apart from each other. As they separate, molten magma from the mantle rises to fill the gap, solidifying to create new crustal material. This process is known as seafloor spreading.

Examples: The Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the North American and Eurasian plates are diverging, creating new oceanic crust and causing the Atlantic Ocean to widen. On continents, divergent boundaries can form rift valleys, such as the East African Rift Valley.

2. Convergent Boundaries:

At these boundaries, plates are colliding. The outcome depends on the types of crust involved:

Oceanic-Oceanic Convergence: When two oceanic plates collide, one is typically forced beneath the other in a process called subduction. This creates deep oceanic trenches and can lead to the formation of volcanic island arcs (e.g., the Mariana Trench and the Japanese archipelago).

Oceanic-Continental Convergence: A denser oceanic plate subducts beneath a less dense continental plate. This results in volcanic mountain ranges along the continent’s edge and deep offshore trenches (e.g., the Andes Mountains and the Peru-Chile Trench).

Continental-Continental Convergence: When two continental plates collide, neither can easily subduct due to their similar low densities. Instead, the immense pressure causes the crust to crumple, fold, and uplift, forming massive, non-volcanic mountain ranges (e.g., the Himalayas, formed by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates).

3. Transform Boundaries:

At these boundaries, plates slide horizontally past each other. Crust is neither created nor destroyed, but the immense friction and stress between the plates can lead to frequent and powerful earthquakes.

Examples: The San Andreas Fault in California, where the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate are grinding past each other, is a famous transform boundary.

The Profound Impact of Tectonic Plates on Earth’s Surface

The ceaseless motion of tectonic plates is responsible for virtually all of Earth’s major geological features and events:

Earthquakes: Shaking of the Earth’s surface caused by the sudden release of energy along fault lines at plate boundaries.

Volcanoes: Formed when magma rises to the surface, often at subduction zones or divergent boundaries.

Mountain Ranges: Created by the immense forces of continental collisions.

Oceanic Trenches: The deepest parts of the oceans, formed by subduction.

Tsunamis: Giant ocean waves often triggered by undersea earthquakes at plate boundaries.

* Continents’ Drift: Over millions of years, plate tectonics have rearranged the continents, forming supercontinents like Pangea, and influencing global climate patterns and the distribution of life.

In essence, tectonic plates are the Earth’s dynamic “skin,” perpetually in motion, shaping and reshaping our planet’s landscapes, dictating where natural hazards occur, and profoundly influencing the long-term evolution of both geology and life.

Understanding these crucial basics of tectonic plates allows us to appreciate the incredible, ongoing processes that make Earth such a vibrant and ever-changing world. It’s a constant reminder that beneath our seemingly stable ground, immense forces are at play, orchestrating a geological masterpiece that continues to unfold.

0 Comments